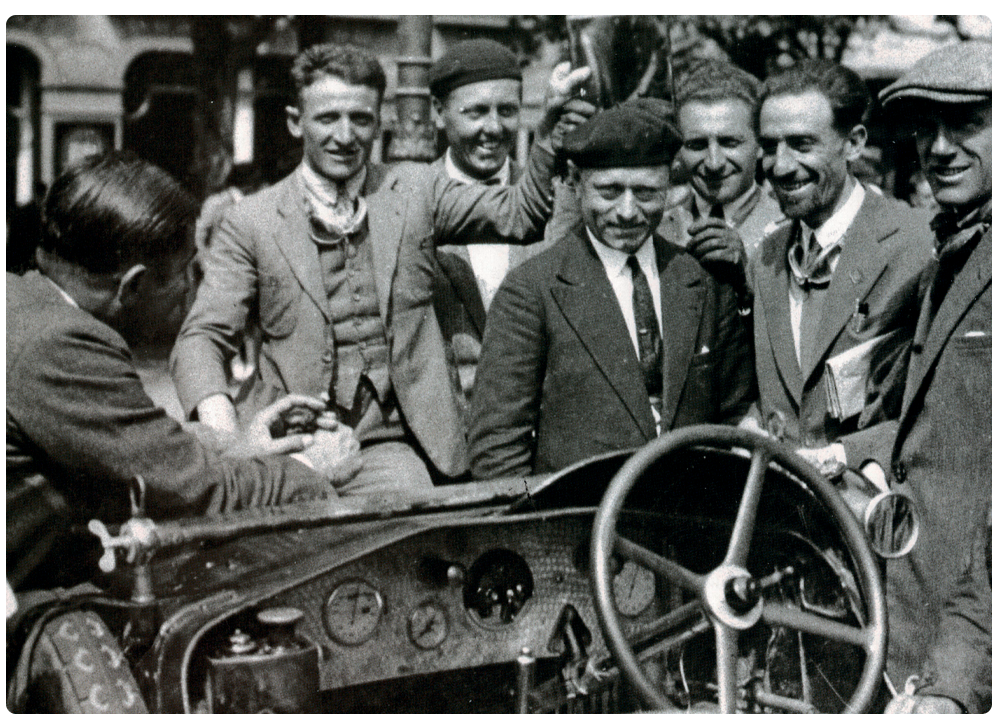

MORANDI – MINOIA

The first winners of 1000 miglia in 1927

***

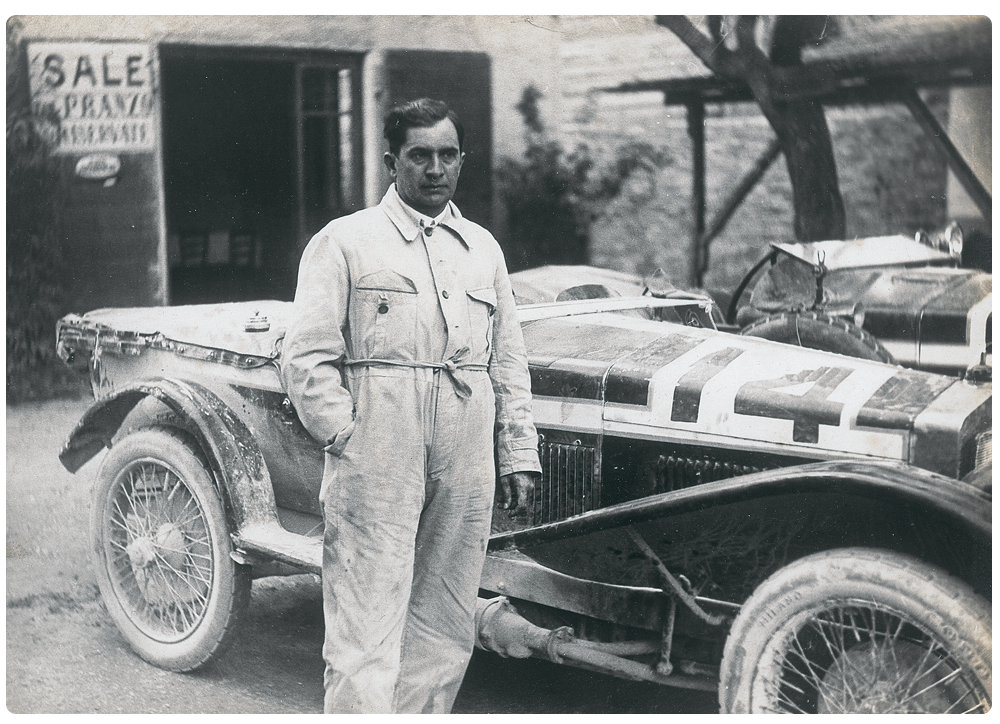

“Nando” Minoia – driving as an art.

02/06/1884 – 28/06/1940

The driver who had characterized the success of the OM Works Team in racing during the 1920s, even though his relationship with the factory from Brescia ended quite abruptly soon after his victory in the first Mille Miglia, because of the corporate reorganization after the crisis of the 1927, was Nando Minoia, the veteran of the Belle Epoque’s Grand Prix, one of the great aces of the Italian motor sport.

The Isotta-Fraschini had prepared a team of four 8 litre cars for the 1907 Targa Florio, which with little modification could be adapted to the rules of the Coppa Florio. The dean of the drivers of this team was the famous Vincenzo Trucco, formerly a Royal House chauffeur. Another driver on it was the 23 year-old son of a Milanese coachman, Ferdinando “Nando” Minoia who had rapidly become a tester in the factory which he had entered as a boy, after an apprenticeship as a bicycle and motorcycle mechanic. In Brescia, Minoia, who had had his racing debut in 1905, and who already had a participation to the Kaiserpreis and to the Targa Florio under his belt, took the lead at the beginning of the race, and although slowed down in the last two laps because of tyre troubles that forced him to drive for the last 20 km on the rim of the front right wheel, easily won from the two Benz of the famous and very experienced Héméry and Hanriot.

Minoia’s performance had been exceptional, but its level appears to have escaped the comprehension of the main commentators. Faroux, for instance, restricted himself to mention the winner’s name adopting the spelling Minoia to make it more palatable for French readers. This destiny of underestimation would mark Minoia’s historiographic fate, who, although the better informed critics among those closer to his era would consider him in the same way as the great Italian pioneers such as Cagno, Lancia e Nazzaro”, was soon exclusively remembered as the winner of the first Mille Miglia, thanks to the legend always sorrounding the Italian race, rather than for an excellent, varied and exceptionally long – he was in fact active in racing from 1905 to 1932 – career of a driver of top international class. Minoia was among the forefathers of those drivers able to excel in every kind of racing, on any kind of ground and at the wheel of any kind of car, of which Stirling Moss would become the sublime example. His mechanical feeling and his “velvet” touch of the steering wheel, unanimously described by those who had experimented it, had made him sought-after by the factories that needed a fine tuning of their new models or wanted a back up driver of great reliability. Taking on such a role, made necessary probably by having embraced racing as his only profession, does not do justice to Minoia’s natural speed in terms of the obtained results. After having driven for Isotta-Fraschini, Lorraine-Dietrich, Storero and Peugeot Italiana before WWI, the following years saw him driving for the works teams of Piat (1921), Mercedes (1921/22), Steyr and Benz (1923), again Steyr and Alfa Romeo (1924), Bugatti (1926/29), Alfa Romeo (1929/32). The longer alliance with O.M., for which he was head-tester from 1924 to 1927 after having raced the cars from Brescia since 1921 and later for some race in 1930, is a case by itself.

The first race meeting in Europe after the awesome bloodbath took place on 24 August 1919 on the unlikely venue of Fan Island, a stretch of sand off the western seashore of Jutland in the North Sea. It was a speed event on the sand, that Minoia won driving a Fiat built for the 1914 Grand Prix de l’ACF. A 7L Mercedes gave him the victory at the Aosta-Gran San Bernardo and a no-penalty run in the Coppa delle Alpi in 1921, after an indifferent Targa Florio driving a 3L GP Fiat. Minoia was not entered by Fiat for the first Italian Grand Prix, so the following year he was signed again by Mercedes, this time for the Targa Florio. Once again he had to give a new model its maiden race; it was a 1500 cc that revealed itself not much powerful, despite using a supercharger for the first time in the factory history, and not reliable. The 1923 and 1924 Targa Florios were raced driving Steyr of 3.3 and 4L. It was an excellent powerful Austrian Grand Touring car, with which Minoia finished third overall in 1923, while retiring for a mechanical illness the following year. Meanwhile, Nando had taken the 4C 1500 O.M. to several victories also abroad, in hillelimbs in Austria and Czechoslovakia. Minoia’s sporting activity would develop more and more outside Italy in the following years: in 1926 the Targa Florio was his only race in Italy. It is possible that this was the reason for a drop of Minoia’s popularity in Italy in those years. Giulio Masetti, for instance, who raced for the British Sunbeam mainly abroad, had been the victim of a campaign of vile shallowness masterminded from high up in the government, that deeply embittered him for the last months of his life inducing him to manifest the intention to retire. In 1926 Meo Costantini, head driver and Bugatti team manager had to reform the works team. Professional driver-testers able to fine-tuning the new models, the sale of which was the only support of the factory in Molsheim, needed to be fielded alongside the fast clients such as Dubonnet, Maggi and the de Vizcayas. Costantini had been able to keep Jules Goux, the only one among the French aces who was free, the others all being engaged with the Delace and Talbot works teams, and signed Minoia for some international race. Nando raced the new unsupercharged 2.3 L T35T but also the 1500 cc T39A, the most restive to tuning among the Grand Prix cars of la marque. A second place in the Targa Florio in a T35T and a fourth and fifth in the Spanish races paid back Molsheim of the granted trust. Minoia became in the years to follow a constant presence in the Bugatti works team at the Targa Florio, the race that more than any other would contribute to the immortal fame of the Alsatian factory. Minoia had become a true specialist.

After the second place in 1926, he retired in 1927 driving a T35C at its racing debut, after having led the race for a long time, was sixth in a T37A in 1928 and second in a T35C in 1929. That year Minoia had finally raced to win. Ferdinando Minoia and Giuseppe Morandi, leading an OM were the first winners of the Millemiglia, taking 21 hours, 4 minutes and 48 seconds to finish the race. The Bugatti works team consisted also of Conelli, of the veteran Wagner, who had started racing three years before Nando, and by the hard and fast driving Albert Divo, the winner of the previous year, all driving 135Cs. Minoia started in front as in 1927, pushed from behind by Borzacchint and then by Divo. A progressive hardening of the steering prevented him to answer to Divo’s attack, who finally won by two minutes, a derisory advantage for the Targa. Minoia kept the fastest lap. He had also won for Bugatti the important Premio Romano del Turismo in 1928, teamed with Foresti, a 20 hour-long race ran on the Tre Fontane cireuit and had finished seventh the German Grand Prix for sports cars, always in a 143. Long-distance races had become a new specialty for Minoia. His successes at the wheel of the O.M.s were in races of this kind and are the centre of our narrative in the previous sections.

It was a reason for surprise to see Minoia starting for the 1928 Mille Miglia at the wheel of an American La Salle, at-ter the victory for O.M. of the year before. The reason was that, together with the driver Balestrero, who shared the car with him, had invested in an Agency for omporting American cars. It did not seem in principle a bad proposition

Soon, though, the import of foreign cars would be severely limited and there was no possibility of succeeding for the enterprise of Minoia and Balestrero, who had to suffer the economical consequences. So, Minoia was forced to carry on with his activity as a “free-lance” driver, called by Alfa Romeo and O.M. mainly for sports car racing, until when, in May 1931 he received a phone call by Vittorio Jano. Luigi Arcangeli’s death during practice for the Italian Grand Prix, had made necessary to find at the last moment a driver for one of the new Alfa Romeo 8C 2300. The FIA of that time (AIACR) had instituted an European Championship for drivers under a point system ” , to be contested in three races, the 1931 Grandes Epreuves, that is the Grands Prix of Italy, ACF and Belgium, all run under a Formule Libre on the distance of 10 hours. Second at Monza with Borzacchini, sixth at Montlhéry with Zehender and third at Spa with Minozzi, Minoia found himself to have become the first European Champion ‘ It was a today forgotten feat, in spite of the prevailing popularity enjoyed by the “Championships” in which the sport is exclusively organized, but that did not go unnoticed then: “…Minoia in a masterful style had marched regularly, deserving the victory of the European Championship».

The commentary of the British magazine The Autocar, besides underlining the international echo of this victory, perfectly summarizes the judgement that can be given about Minoia’s career: “It is good that Minoia should have secured the European championship for 1931 as a result of the Grand Prix at Spa the other day, for Minoia has been in the game for many years, but seems never quite to have got full and proper recoénition of his ability.” I Minoia carried on racing for Alfa Romeo until the Le Mans 24 hours race in 1932, when he came out unhurt from a bad accident at the Maison Blanche that induced him to retire from racing. It is possible that his aplomb was undermined. He remained with Alfa Romeo, more as a demonstrator than a tester, or, as it was written, “as an enthusiast about the problems of racing cars. His touch of the wheel still made him very much requested for showing new cars to the press or to the concessionaries.

There are almost no testimonies about his last years of life. The journalist Canestrini reports one, rather dim. Fe-lice Nazzaro and Nando Minoia were good friends and Nazzaro often would come to Milan to visit him. They met, sometimes in the presence of Canestrini, in a “restaurant near San Siro”101 , where these gentlemen, who had just gone over fifty, let themselves go to idle talk as if they were old retirees, such as who was better between Nuvolari or Varzi, who had been the fastest driver ever or how useful the riding mechanic had been to form new drivers, chats that Canestrini scrupolously took down.

Nando Minoia died during the summer of 1940, for the after-effects of a thrombosis that had hit him the year before and that had weakened him. “His unequalled style of driving” was still highlighted in the obituaries. A vivid description of his qualities as a driver, given after his victory at the 1923 Coppa delle Alpi del 1923, most of any other hits the nail on the head: “a self-confident, serene, infallible driver”.

Inspired by this fascinatic world of wheels and speed Paul Picot created a special limited model.

Since 2013 Paul Picot is in partneship with Morandi Classic Car in Castiglione delle Stiviere (BS) C.A.M.S.C. to create every year the very exclusive event on Garda Lake.

Automatic movement entirely hand finished, showing the hours and minutes. Chronograph functions: centre second hand, minute counter at 12 o’clock and tachymeter scale. Black dial with white counters inspired by the instrumentation of the OM Superba racing car. Screw-down crown, spherical shape sapphire crystal, water-resistant to 50 meters. Hand-sewn crocodile strap or metal bracelet. Limited Edition of 100 pcs.